Cortisol is often called the “stress hormone,” and when it stays elevated, it can be problematic for heart health. If you’re wondering how to reduce cortisol, it’s important to first understand how it affects your cardiovascular system.

What is Cortisol?

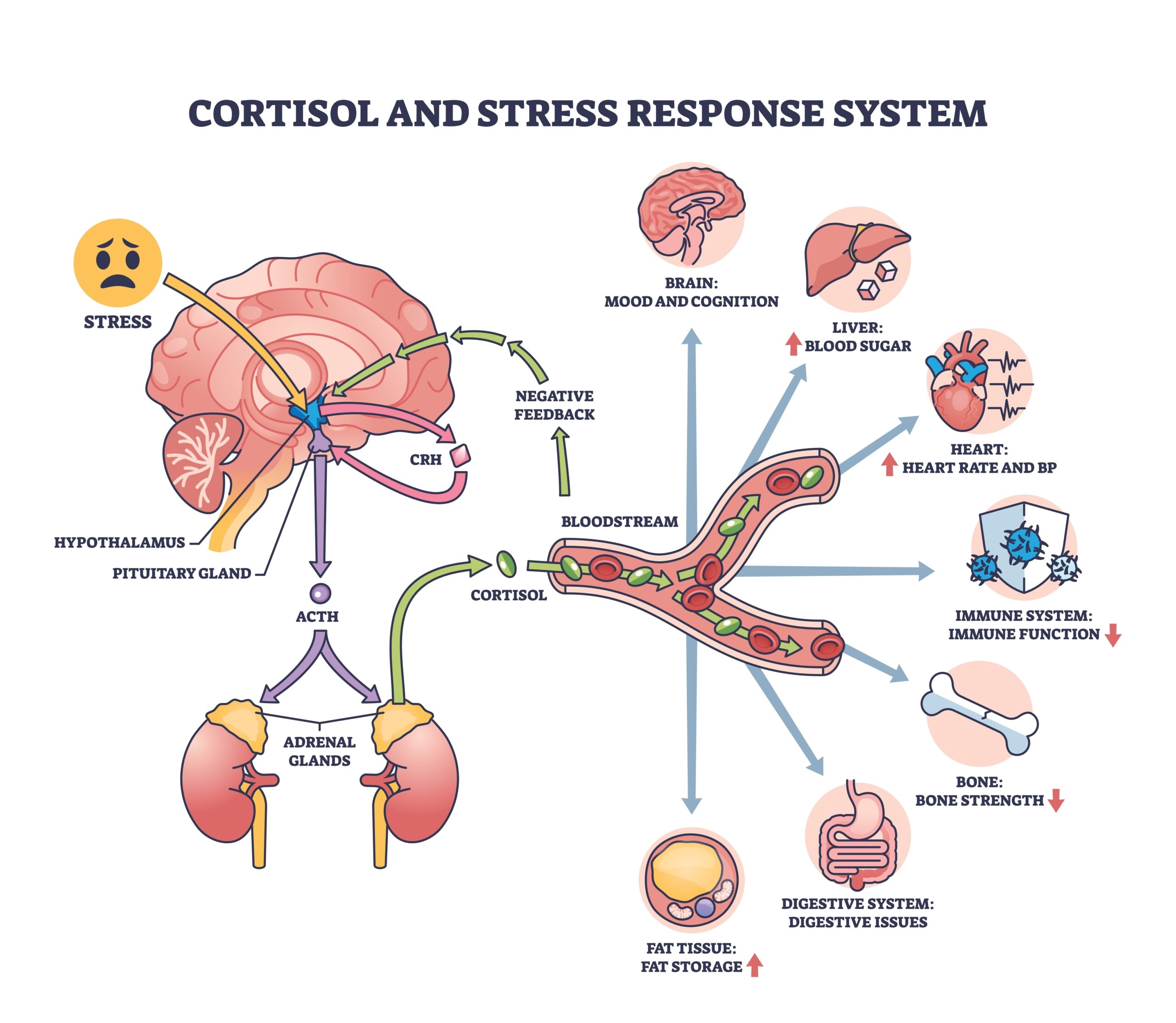

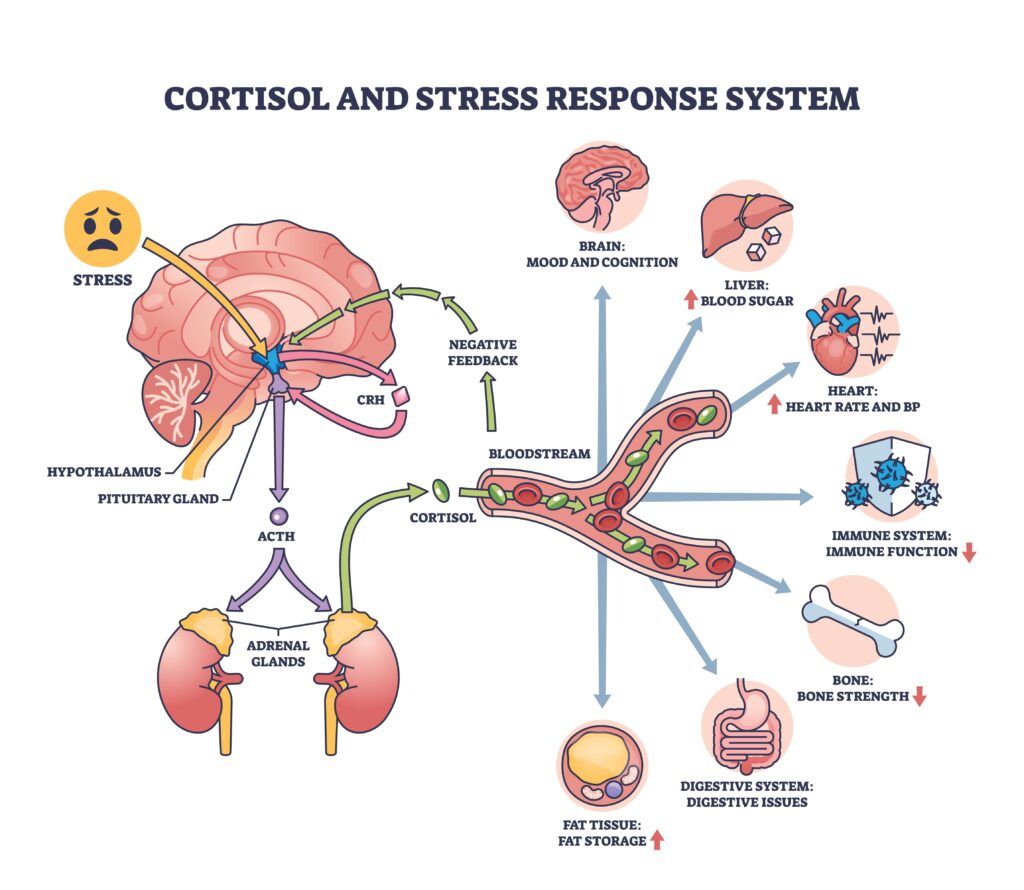

Cortisol interacts with the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, a communication network between your brain and adrenal glands, and is released in response to physical, emotional, and environmental stress.

While it often gets a bad rep, cortisol plays essential roles in the short term, helping regulate your blood sugar, inflammation, metabolism, and even sleep. Problems arise when it’s chronically high due to ongoing stress or a cortisol disorder like Cushing’s syndrome.

This can contribute to high blood pressure, insulin resistance, inflammation, accumulation of belly (visceral) fat, sleep disruption, and changes in blood fats, all of which increase the risk of heart disease over time.

Under normal conditions, cortisol follows a daily (circadian) rhythm. Levels naturally peak in the early morning to help you feel alert. It gradually declines and reaches its lowest point late in the evening, to help you prepare for sleep. Working out, being sick, and caffeine intake can cause temporary spikes, which is normal.

Cortisol levels can also have significant variability, depending on time of day, recent stress, sleep quality, illness, and even anxiety. They can be tested via blood, urine, or saliva, and your clinician may recommend a combination of these. They may also want to check cortisol twice in one day or multiple times over several days to capture your average cortisol pattern.

How High Cortisol Affects Heart Health

Chronically elevated cortisol doesn’t just affect how you feel. It puts your heart under a constant metabolic, inflammatory, and vascular stress, which can contribute to the development of cardiometabolic diseases.

Here’s how:

- Raises blood pressure. Cortisol boosts the effects of catecholamines (like adrenaline), which cause blood vessels to constrict. This makes your heart work harder to pump blood, increasing blood pressure. It also increases sodium uptake, putting stress on your kidneys, promoting fluid retention, and further increasing blood pressure.

- Promotes endothelial dysfunction. Ongoing high cortisol disrupts your normal immune function. This eventually damages the endothelium, which is the protective lining of your blood vessels, making you more vulnerable to atherosclerosis and hypertension.

- Impairs blood sugar control. Cortisol tells your liver to release more sugar into the bloodstream while making it harder for your muscles and other cells to take that sugar in and use it for energy. So, as blood sugar levels remain high, this tells your pancreas to continue releasing insulin, which your cells become less responsive to over time. The strain increases your risk of type 2 diabetes and blood vessel damage, which compounds your cardiovascular risk.

- Affects blood fats. High cortisol shifts lipid metabolism in a way that favors cardiovascular disease, increasing the release of fatty acids into the bloodstream. It can lead to more LDL and triglycerides as well as reduced HDL, creating an atherogenic profile that promotes the buildup of plaques in your arteries.

- Encourages belly fat accumulation. Visceral fat tissue has a high density of cortisol receptors. Unlike the fat right under your skin, this type of fat surrounds your vital organs, is metabolically active, and has a pro-inflammatory effect over time. This can worsen insulin resistance and increase the risk of heart disease.

Signs Your Cortisol May Be Elevated

Cortisol fluctuates throughout the day, but when levels stay high, your body often sends warning signals.

These symptoms don’t confirm elevated cortisol on their own, but patterns may suggest ongoing stress hormone dysregulation, which warrants a conversation with your healthcare provider:

- Trouble sleeping. High cortisol interferes with normal melatonin release, making it harder to fall asleep and/or stay asleep through the night.

- Constant fatigue. An odd sense of being “wired but tired” can happen when high cortisol during the day provides a false sense of alertness when your nervous system is actually fatigued.

- Increased belly fat. Central fat distribution becomes concerning for cardiometabolic risk when the waist-to-hip ratio exceeds 0.90 in men or 0.85 in women, or when the waist circumference is greater than 40 inches for men or 35 inches for women in the US and Europe. For Asian populations, these numbers are 35 inches for men and 31 inches for women.

- Frequent salt or sugar cravings. We all have occasional cravings, but because cortisol raises blood sugar and can influence your appetite-regulating hormones, you may notice a desire for quick-energy, ultra-processed foods more than normal.

- Anxiety or irritability. High cortisol keeps your nervous system in a heightened fight-or-flight mode, which can show up as a short temper, reactivity, or trouble relaxing.

- High blood pressure. Cortisol increases blood vessel constriction and fluid retention, which can increase your blood pressure levels despite otherwise healthy habits.

- Irregular menstrual cycles. Cortisol fluctuates during the menstrual cycle. Having excess cortisol may affect reproductive hormone production, suppressing estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone. For women, this might look like irregular or missed periods.

How to Lower Cortisol Naturally

We can’t avoid every stressor, so lowering cortisol isn’t about eliminating stress. Instead, it’s about supporting a healthy stress response and more resilience to stress overall. The most effective approaches to how to reduce cortisol are those supporting circadian rhythms, blood sugar stability, and nervous system recovery.

Prioritize Sleep Hygiene

Sleep is one of the strongest regulators of cortisol, so it’s important to get consistent, good-quality rest. Adults should aim for 7-9 hours per night. Try to follow a regular sleep-wake schedule, create a sleep-promoting environment in your bedroom, and avoid sleep disruptors close to bedtime, like screens, heavy meals, alcohol, and caffeine.

Build Stress Management Practices

If you often feel stressed, first try to identify some of your biggest triggers. From there, think about how you can set boundaries around things like time, work, relationships, and digital use. Some simple practices can include a 5-minute meditation session, deep breathing, journaling, or taking nature walks to move your body from fight-or-flight to rest-and-digest.

Optimize Your Nutrition

Nutritional quality and adequacy matter for both hormone regulation and overall wellness. Undereating, skipping meals, or chronically low protein intake can contribute to increased cortisol. A balanced, heart-healthy diet is based on eating adequate nutrition to meet your specific needs based on your age, gender, medical history, medications, risk, etc. Work with a Registered Dietitian who can personalize your diet plan to ensure nutrient adequacy.

Move Your Body Mindfully

Regular, intentional physical activity can help lower your resting cortisol levels. Try moderate-intensity activities that add up to 150-300 minutes per week, including various things like walking, strength training, yoga, and cycling. While exercise does cause a temporary cortisol spike, studies show that it helps reduce your cortisol response to stressful situations later, assuming you’re moving your body regularly.

But when you’re working out too intensely (say, over an hour 7 days a week, pushing yourself without adequate recovery), especially when this is combined with poor sleep, inadequate calorie intake, or an otherwise stressful lifestyle, this can encourage chronically high cortisol.

Evaluate Your Caffeine and Alcohol Habits

Caffeine stimulates cortisol when consumed in large amounts and can make it harder to go to bed if you drink it later in the day. Alcohol, while it may be initially calming, is known to be a potent sleep disruptor, increasing nighttime cortisol and inhibiting recovery.

Eat in Circadian Alignment

Cortisol is tightly aligned to your internal clock, so eating irregularly, late at night, or skipping meals can contribute to erratic cortisol rhythms. Aim to eat earlier in the day and at fairly regular intervals, avoiding heavy late-night meals. Doing so can help support healthier cortisol patterns, better blood sugar control, and heart health.

FAQs About Cortisol and Heart Disease

What supplements lower cortisol?

Several supplements have been studied for their ability to reduce inflammation and possibly support healthy cortisol levels. Some of the most well-researched include ashwagandha, holy basil, omega-3s, and rhodiola. These supplements may help reduce inflammation and stress response, but they work best when paired with lifestyle habits like consistent sleep, regular movement, and a nutrient-dense diet.

Still, remember that doses, labs, medications, and your medical history need to be assessed before just taking anything; working with your registered dietitian can help. Some supplements come with a higher risk of harm or even liver damage, especially when taken in large amounts, so it’s good practice to choose third-party tested supplements (e.g., NSF International, USP) to ensure quality, purity, and safer options.

How long does it take to lower cortisol naturally?

Cortisol changes gradually as you start implementing healthier lifestyle habits. Some people notice improvements within a couple of weeks of consistent habits like better sleep, walking, or reducing caffeine. But for long-term, measurable reductions, especially if cortisol has been high for months, it often takes several weeks of lifestyle changes and/or targeted supplementation. Cortisol follows a daily rhythm, so consistency is more important than intensity.

Can high cortisol really increase the risk of heart disease?

Yes. Chronically elevated cortisol can raise blood pressure, increase inflammation, worsen blood sugar control, promote visceral belly fat, and negatively impact cholesterol, all of which elevate the risk of heart disease. Over time, unmanaged stress hormones can strain the cardiovascular system just as significantly as poor diet or lack of exercise.

The Bottom Line

Chronic stress and persistently elevated cortisol can quietly work against cardiovascular health by driving inflammation, blood pressure changes, insulin resistance, and visceral fat accumulation. However, cortisol is responsive to everyday habits, so looking at your whole lifestyle and its effects on your heart health is key.

By addressing cortisol issues at their root, you’re actively protecting your heart as well as reducing stress. If you’re interested in help looking at the whole picture of your heart health, including science-based nutrition and lifestyle, book a call with me or learn about my Optimize group program.

Sources

- Tóth-Mészáros, A., Garmaa, G., Hegyi, P., Bánvölgyi, A., Fenyves, B., Fehérvári, P., Harnos, A., Gergő, D., Nguyen Do To, U., & Csupor, D. (2023). The effect of adaptogenic plants on stress: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Functional Foods, 108, 105695. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jff.2023.105695

- Oravcova, H., Katrencikova, B., Garaiova, I., Durackova, Z., Trebaticka, J., & Jezova, D. (2022). Stress Hormones Cortisol and Aldosterone, and Selected Markers of Oxidative Stress in Response to Long-Term Supplementation with Omega-3 Fatty Acids in Adolescent Children with Depression. Antioxidants, 11(8), 1546. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox11081546

- Lopresti AL, Smith SJ, Metse AP, Drummond PD. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial investigating the effects of an Ocimum tenuiflorum (Holy Basil) extract (HolixerTM) on stress, mood, and sleep in adults experiencing stress. Front Nutr. 2022;9:965130. Published 2022 Sep 2. doi:10.3389/fnut.2022.965130 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9524226/

- Della Porta M, Maier JA, Cazzola R. Effects of Withania somnifera on Cortisol Levels in Stressed Human Subjects: A Systematic Review. Nutrients. 2023;15(24):5015. Published 2023 Dec 5. doi:10.3390/nu15245015 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38140274/

- Caplin A, Chen FS, Beauchamp MR, Puterman E. The effects of exercise intensity on the cortisol response to a subsequent acute psychosocial stressor. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2021;131:105336. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2021.105336 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34175558/

- Stachowicz, M., Lebiedzińska, A. The effect of diet components on the level of cortisol. Eur Food Res Technol 242, 2001–2009 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00217-016-2772-3

- Amanzholkyzy A, et al. (2025). Stress-related changes in the menstrual cycle and their significance for health: a literature review. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/393351549_Stress-related_changes_in_the_menstrual_cycle_and_their_significance_for_health_A_literature_review

- Chao AM, Jastreboff AM, White MA, Grilo CM, Sinha R. Stress, cortisol, and other appetite-related hormones: Prospective prediction of 6-month changes in food cravings and weight. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2017;25(4):713-720. doi:10.1002/oby.21790 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28349668/

- UCLA Health. (2025). Feeling tired but wired? Here’s what might be causing it. https://www.uclahealth.org/news/article/feeling-tired-wired-heres-what-might-be-causing-it

- Monteleone P, Fuschino A, Nolfe G, Maj M. Temporal relationship between melatonin and cortisol responses to nighttime physical stress in humans. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1992;17(1):81-86. doi:10.1016/0306-4530(92)90078-l https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1609019/

- NIDDK. (2018). Cushing’s syndrome. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/endocrine-diseases/cushings-syndrome#symptoms

- Kolb H. Obese visceral fat tissue inflammation: from protective to detrimental?. BMC Med. 2022;20(1):494. Published 2022 Dec 27. doi:10.1186/s12916-022-02672-y https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36575472/

- Lee, M., Pramyothin, P., Karastergiou, K., & Fried, S. K. (2014). Deconstructing the roles of glucocorticoids in adipose tissue biology and the development of central obesity. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) – Molecular Basis of Disease, 1842(3), 473-481. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.05.029

- Ortiz R, et al. (2022). Cortisol and cardiometabolic disease: a target for advancing health equity. https://www.cell.com/trends/endocrinology-metabolism/abstract/S1043-2760%2822%2900161-8

- Beaupere, C., Liboz, A., Fève, B., Blondeau, B., & Guillemain, G. (2021). Molecular Mechanisms of Glucocorticoid-Induced Insulin Resistance. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(2), 623. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22020623

- Akaza I, Yoshimoto T, Tsuchiya K, Hirata Y. Endothelial dysfunction aassociated with hypercortisolism is reversible in Cushing’s syndrome. Endocr J. 2010;57(3):245-252. doi:10.1507/endocrj.k09e-260 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20023367/

- American Heart Association. (2021).Elevated stress hormones linked to higher risk of high blood pressure and heart events. https://newsroom.heart.org/news/elevated-stress-hormones-linked-to-higher-risk-of-high-blood-pressure-and-heart-events

- El-Farhan N, Rees DA, Evans C. Measuring cortisol in serum, urine and saliva – are our assays good enough?. Ann Clin Biochem. 2017;54(3):308-322. doi:10.1177/0004563216687335 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28068807/

- Liu PY. Rhythms in cortisol mediate sleep and circadian impacts on health. Sleep. 2024;47(9):zsae151. doi:10.1093/sleep/zsae151 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11381560/

- Thau L, Gandhi J, Sharma S. Physiology, Cortisol. [Updated 2023 Aug 28]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538239/

- Knezevic E, Nenic K, Milanovic V, Knezevic NN. The Role of Cortisol in Chronic Stress, Neurodegenerative Diseases, and Psychological Disorders. Cells. 2023;12(23):2726. Published 2023 Nov 29. doi:10.3390/cells12232726 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10706127/

- Fraser R, Ingram MC, Anderson NH, Morrison C, Davies E, Connell JM. Cortisol effects on body mass, blood pressure, and cholesterol in the general population. Hypertension. 1999 Jun;33(6):1364-8. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.33.6.1364. PMID: 10373217. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10373217/