The terms “heart attack” and “cardiac arrest” are often used interchangeably, but they’re not the same thing. A heart attack is a circulation problem, while cardiac arrest is an electrical malfunction, and they’re both serious issues that require immediate medical attention.

Understanding the difference between cardiac arrest and heart attack can help you recognize symptoms faster, respond appropriately, and potentially save a life.

Heart Attack vs. Cardiac Arrest: What Are They?

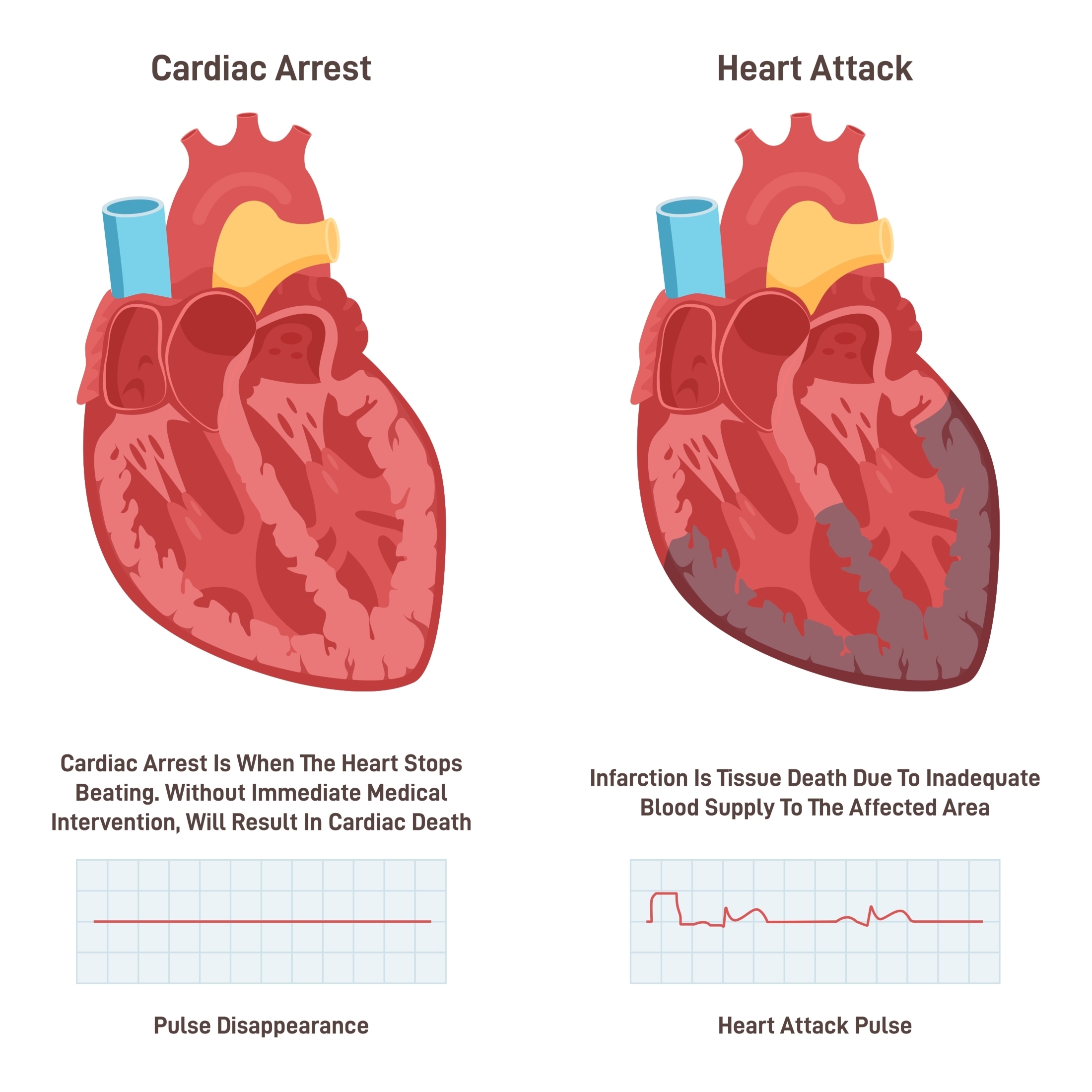

Heart attacks and cardiac arrests are often confused, but they have important differences. A heart attack happens when blood flow to the heart is blocked, while cardiac arrest is an electrical problem that causes the heart to suddenly stop beating.

According to the CDC, nearly 805,000 Americans have a heart attack each year, while more than 356,000 experience an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest.

Understanding how these two events vary can be a matter of life and death, so keep reading for a more detailed look at them.

Key Differences Between Cardiac Arrest and Heart Attack

Whether you’ve experienced a cardiovascular event or already know that you’re at a higher risk for one, a good place to start is knowing cardiac arrest vs heart attack symptoms and risk factors.

Heart Attack

A heart attack occurs when there’s a partial or total blockage in the artery that brings blood and oxygen to your heart. Arteries can become blocked when fatty deposits called plaque accumulate, restricting blood flow and the transport of oxygen. Without oxygen and essential nutrients, heart muscle cells experience damage or death.

This buildup of plaque is also known as atherosclerosis and happens over time. The good news is that having a heart attack is largely preventable through awareness of your risk factors, practicing healthy lifestyle habits, and working closely with your healthcare team.

Symptoms of a heart attack can include:

- Shortness of breath

- Chest discomfort that lasts more than a few minutes

- Nausea

- Lightheadedness

- Experiencing a cold sweat

- Pain or discomfort in the jaw, stomach, neck, or one or both arms

Note that symptoms can vary between men and women. To learn more about heart attacks, including diagnosis, treatment, and prevention, check out my blog post What is a Heart Attack? Facts and Statistics.

Risk factors for having a heart attack include:

- High blood pressure, which damages arteries

- High cholesterol, particularly high LDL and non-HDL cholesterol

- Smoking damages the lining of your arteries and increases plaque formation

- Diabetes, which can damage blood vessels over time if not well-managed

- Obesity, as excess weight increases strain on your heart

- Sedentary lifestyle

- Nutritionally-poor diet, high in saturated and trans fats, and added sugars

- Family history of heart disease

- Age, especially for men over 45 and women over 55

Cardiac Arrest

Unlike a heart attack, cardiac arrest results from an electrical malfunction. This causes your heart to stop beating or to beat so fast that it stops pumping blood.

When someone experiences cardiac arrest, they often collapse, becoming unconscious and unresponsive. Cardiac arrest can happen in someone who may or may not have a diagnosis of heart disease.

Sudden cardiac arrest can also occur. This may either result from an electrical problem or from the heart arteries becoming too clogged with fatty buildup, impeding blood flow.

Sudden cardiac death is caused by cardiac arrest and loss of heart function. When sudden cardiac arrest occurs, your organs — including your brain and heart — cannot receive oxygen and die without immediate medical attention. Death generally occurs within one hour of onset if not addressed quickly, though many people can be revived.

Having other heart conditions, such as cardiomyopathy, arrhythmias, Afib, long QT syndrome, and heart failure, can disrupt the heart’s natural rhythm and lead to sudden cardiac arrest.

Risk factors for cardiac arrest include:

- Having coronary artery disease, caused by atherosclerosis (plaque buildup in the arteries) that reduces blood flow to the heart

- Previous heart attack, which can cause damage and weaken the heart muscle, triggering arrhythmias

- Arrhythmias, or irregular heartbeats, are electrical disturbances

- Congenital heart defects, or structural issues present from birth

- Heart failure, as a weakened heart muscle cannot pump blood efficiently, increasing the risk of arrest

- Severe blood loss or trauma, which can interrupt the heart’s electrical system

- Substance use, as excessive alcohol or drug use, can trigger arrhythmias

- Experiencing a sudden forceful impact to the chest (called commotio cordis)

Can a Heart Attack Lead to Cardiac Arrest?

While heart attacks and cardiac arrest are two distinct events with different causes, they are associated. Most heart attacks don’t cause cardiac arrest, but they can raise the risk, as cardiac arrest can happen following a heart attack or during recovery from one.

Prevention Tips for Heart Health

What’s most important to understand about having a heart attack vs cardiac arrest is how to practice prevention. Optimizing your heart health requires preventive daily lifestyle habits as well as getting regular wellness exams and working closely with your healthcare team, including a cardiovascular dietitian, to address any risk factors.

Improving Your Nutrition

Heart attacks are caused when plaque builds up in the arteries and restricts or prevents blood flow. It’s important to address the underlying root causes of this, such as inflammation, oxidative stress, insulin resistance, and blood vessel dysfunction, which can largely be improved through science-based nutrition.

For example, one would want to minimize or avoid foods that are known to contribute to plaque formation. This includes foods high in saturated fat, such as eggs, dairy, beef, coconut oil, and palm oil.

Instead, focus on foods that are rich in fiber, like fruits, vegetables, and whole grains, unsaturated fats like avocado, nuts, and seeds, and nitrates that can open blood vessels, like beets. The therapeutic doses will depend on the individual, which is why personalized, science-based nutrition is key to results and success.

There is evidence of a strong connection between your gut health and heart health, indicating that some digestive issues can even lead to arrhythmias and atherosclerosis.

Nutrition is crucial for keeping your heart in sinus rhythm (the normal, steady heartbeat your body relies on). A diet rich in fiber, antioxidants, and plant-based foods supports a healthy gut microbiome, which helps regulate inflammation and heart rhythm.

Eating low-sodium, high-potassium meals can manage blood pressure and prevent strain. And ensuring you get enough magnesium, potassium, and omega-3s can help prevent arrhythmias and support heart function overall.

Awareness of Your Family History

Understanding family and personal health history: Being aware of abnormal heart rhythms in your family can help determine whether you should undergo genetic testing for issues that may cause arrhythmia.

Additionally, being aware of inherited genetic markers, such as high Lipoprotein (a), can help you take a more proactive stance to optimize your lab values. This should be taken into account along with other personal risk factors, such as blood pressure readings and other blood lipids like triglycerides, that you can begin to take under control.

Sleep Quality and Consistency

Some research has found that people who undergo extreme inconsistencies in their sleep duration are at an increased risk of having a heart attack. Specifically, one 2019 study found that getting fewer than 6 hours or more than 9 hours of sleep per night is associated with a higher heart attack risk, independent of other factors.

Managing Your Stress Levels

There is evidence that mental stress can promote ventricular fibrillation and arrhythmia, which can lead to cardiac arrest. Furthermore, anxiety may play some role in sudden cardiac arrest due to its contribution to other risk factors like heart disease.

Stress is an inevitable part of life, but learning how to minimize its effects on your mental health is key, through things like physical activity, making time for hobbies you enjoy, and communicating with your social support system.

If you’re looking to reduce your risk of having a heart attack or cardiac arrest, I would love the opportunity to meet with you for 1:1 nutrition counseling. I also offer a group program called Optimize, where we work together to understand your heart health and improve your risk factors.

Whether you’re living with heart disease risk factors, have had a heart attack, or are otherwise concerned about heart failure, I can help you take the reins of your diet and lifestyle to make positive changes. Schedule a 15-minute complimentary discovery call to discuss more.

Client Success Story

Knowing your risk factors and taking control of them is the best thing you can do to protect your heart. One of my clients stands out. He had a history of both events, had multiple risk factors, and wanted to take protective steps.

At 63, he came to see me because he was in heart failure (ejection fraction 20%), and wanted to improve it. He had previously sustained 2 heart attacks with stent placements and 2 cardiac arrests prior, with a defibrillator in place. He had a history of high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and atrial fibrillation, which placed him at high risk for these conditions.

At this time, he was on over 10 medications. He felt lethargic and worn down all day long. He would wake up exhausted and have to come home to take a nap in the middle of the day.

We worked closely together in my VIP intensive program.

It was apparent that he was nutrient deficient and had underlying root causes of heart disease, from inflammation to insulin resistance. I helped guide him through science-based nutrition and created a personalized health resource guide and meal plan for him. We focused on what to add to his diet to optimize his heart function.

In just one month’s time, he had no Afib episodes, his defibrillator never went off, he was off of 2 of his blood pressure medications, and he gained his energy back, where he could go the whole day without napping! In 3 months’ time, his cholesterol was optimized (LDL less than 70mg/dL), and his blood sugar levels were optimal (HbA1c less than 5.4%). In 6 months’ time, his ejection fraction went up by 30% to 50%!

He has gained his energy back and feels more confident in his nutrition choices. This should be an empowering story of optimizing heart health, even when faced with multiple risk factors and previous complications.

Heart Attack vs Cardiac Arrest: The Bottom Line

Heart attacks and cardiac arrests are both life-threatening heart emergencies, but they are not the same thing. A heart attack is a blockage issue that disrupts circulation, while cardiac arrest is an electrical issue that stops the heart.

Want to protect your heart health and lower your risk for cardiovascular events? I can help. Learn about my Optimize group program or my 1:1 nutrition counseling services. Have other questions? Click here to schedule a complimentary call.

Sources

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). Heart Disease Facts. https://www.cdc.gov/heart-disease/data-research/facts-stats/index.html

- Fang J, Luncheon C, Ayala C, Odom E, Loustalot F. Awareness of Heart Attack Symptoms and Response Among Adults – United States, 2008, 2014, and 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019 Feb 8;68(5):101-106. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6805a2. PMID: 31851653; PMCID: PMC6366680. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31851653/

- Patel K, Hipskind JE. Cardiac Arrest. 2023 Apr 7. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan–. PMID: 30521287. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30521287/

- NIH. (2022). Heart Attack Causes and Risk Factors. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/heart-attack/causes

- Kumar A, Avishay DM, Jones CR, Shaikh JD, Kaur R, Aljadah M, Kichloo A, Shiwalkar N, Keshavamurthy S. Sudden cardiac death: epidemiology, pathogenesis and management. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2021 Mar 30;22(1):147-158. doi: 10.31083/j.rcm.2021.01.207. PMID: 33792256. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33792256/

- Yu E, Malik VS, Hu FB. Cardiovascular Disease Prevention by Diet Modification: JACC Health Promotion Series. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Aug 21;72(8):914-926. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.02.085. PMID: 30115231; PMCID: PMC6100800. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6100800/

- Nagpal AK, Pundkar A, Singh A, Gadkari C. Cardiac Arrhythmias and Their Management: An In-Depth Review of Current Practices and Emerging Therapies. Cureus. 2024 Aug 9;16(8):e66549. doi: 10.7759/cureus.66549. PMID: 39252710; PMCID: PMC11381938. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11381938/

- Gallucci G, Tartarone A, Lerose R, Lalinga AV, Capobianco AM. Cardiovascular risk of smoking and benefits of smoking cessation. J Thorac Dis. 2020 Jul;12(7):3866-3876. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2020.02.47. PMID: 32802468; PMCID: PMC7399440. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7399440/

- Melo L, Patail H, Sharma T, Frishman WH, Aronow WS. Commotio Cordis: A Comprehensive Review. Cardiol Rev. 2025 May-Jun 01;33(3):256-259. doi: 10.1097/CRD.0000000000000611. Epub 2023 Sep 20. PMID: 37729588. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37729588/

- Rhainds D, Brodeur MR, Tardif JC. Lipoprotein (a): When to Measure and How to Treat? Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2021 Jul 8;23(9):51. doi: 10.1007/s11883-021-00951-2. PMID: 34235598. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34235598/

- Daghlas I, Dashti HS, Lane J, Aragam KG, Rutter MK, Saxena R, Vetter C. Sleep Duration and Myocardial Infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019 Sep 10;74(10):1304-1314. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.07.022. PMID: 31488267; PMCID: PMC6785011. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31488267/

- Batelaan NM, Seldenrijk A, van den Heuvel OA, van Balkom AJLM, Kaiser A, Reneman L, Tan HL. Anxiety, Mental Stress, and Sudden Cardiac Arrest: Epidemiology, Possible Mechanisms and Future Research. Front Psychiatry. 2022 Feb 3;12:813518. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.813518. PMID: 35185641; PMCID: PMC8850954. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35185641/

- Chang Liu M, Tester MA, Franciosi S, Krahn AD, Gardner MJ, Roberts JD, Sanatani S. Potential Role of Life Stress in Unexplained Sudden Cardiac Arrest. CJC Open. 2020 Nov 10;3(3):285-291. doi: 10.1016/j.cjco.2020.10.016. PMID: 33778445; PMCID: PMC7984995. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7984995/