Cholesterol is a waxy substance made by your liver and found in all of your cells, especially the brain and spinal cord. It’s a type of lipid or fatty compound.

Even though too much cholesterol is bad for your health, it serves many important functions, such as in steroid and sex hormone production, cell membrane structure, vitamin D synthesis, and fat digestion and absorption. Having too much can increase the risk of a heart attack.

Does High Cholesterol Cause Heart Attacks?

High cholesterol levels are a direct risk factor for a heart attack.

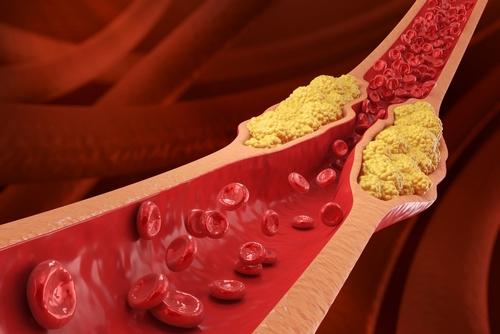

This process begins with plaque formation (cholesterol build-up) in the arteries – an active process that starts with high LDL-cholesterol levels. When there’s too much LDL in the blood that’s not being cleared out, it starts to accumulate in the arteries, causing them to become hardened and narrowed.

When combined with inflammation and oxidative stress, a cascade of further plaque growth, rupture, and artery narrowing occurs. If this continues, a complete artery blockage can occur, leading to a heart attack.

The key to preventing this sequence of events is controlling the blood levels of several markers, such as LDL and non-HDL cholesterol, ApoB, and triglyceride levels.

While it’s a widespread myth that people who have low LDL don’t have heart attacks, studies show a linear relationship between LDL and ApoB. However, ApoB is a structural component of low-density LDL, very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL), and intermediate-density lipoprotein (IDL). All of these are atherogenic.

Even if your LDL appears normal, you can have discordance where there’s also high ApoB. Having ApoB is a prerequisite for making plaque, and its presence increases the risk of heart disease and stroke.

Read more about apolipoprotein B here.

The way plaque forms in your arteries is complex and silent. It can be brewing for decades and is a multi-stage process, starting with endothelial dysfunction. This causes a tear in the artery wall from inflammation or high blood pressure, allowing atherogenic LDL in, which becomes oxidized and triggers an inflammatory process, causing hardened plaque formation.

Heart Attack Cholesterol Levels

Can borderline high cholesterol cause a heart attack? Sure, but there’s more to the story — and the types of cholesterol. There are three main types in blood, also known as lipoproteins (because they’re made of protein and lipids):

- HDL: Known as high-density lipoprotein or “good” cholesterol. It’s good because it’s protective of your heart and helps remove the artery-clogging forms of cholesterol from your bloodstream. Note that having high HDL does not counteract having high LDL, as LDL is more atherogenic regardless.

- LDL: Known as low-density lipoprotein or “bad” cholesterol. It’s more damaging because it leads to more plaque formation. There are several types of low-density lipoproteins, such as very-low-density lipoproteins (VLDL) and intermediate-density lipoproteins (IDL) that eventually transform into LDL. Each LDL particle carries a protein called apolipoprotein B (ApoB), which helps it stick to blood vessel walls and is an important marker of heart disease risk.

- Non-HDL: This includes all of the artery-clogging lipoproteins combined, such as LDL, VLDL, and IDL. Non-HDL levels give us insight into the level of plaque-forming cholesterol you have in your bloodstream. In a bloodwork report, this non-HDL number is your total cholesterol minus your HDL cholesterol level. Additionally, your non-HDL is a surrogate marker for ApoB if you don’t have an ApoB level.

Of course, it’s not just your cholesterol levels that determine heart attack risk. Inflammation, blood pressure levels, insulin resistance, and overall metabolic health are also factors.

Hyperlipidemia vs Hypercholesterolemia

You may hear the terms hyperlipidemia and hypercholesterolemia used interchangeably, but they’re not quite the same. Hypercholesterolemia refers specifically to high cholesterol, particularly LDL, while hyperlipidemia is broader and includes elevated levels of all blood fats, including cholesterol and triglycerides. Understanding both is important, as each can independently raise your risk for a heart attack.

To learn more about these types of cholesterol and other heart health biomarkers, check out my post on understanding your cardiac panel results.

Dietary Risk Factors for High Cholesterol

Traditionally, if your cholesterol levels were high, the top recommendation was to limit dietary cholesterol intake to 300 mg/day. However, dietary cholesterol is no longer thought to be the primary driver of high blood cholesterol levels.

Several studies have not found a link between cholesterol intake in the diet and blood cholesterol levels. Due to this lack of evidence, the recommendation to limit cholesterol was removed from the 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans.

Research shows that when a healthy individual eats dietary cholesterol, the liver will regulate how much cholesterol it needs to make and stop producing more. In a small subgroup of individuals, some may be a hyper absorber of cholesterol and it may need to be further limited.

Instead of focusing solely on cholesterol intake, it’s recommended to focus more on limiting the following for healthy cholesterol levels (especially if you don’t eat much fiber):

- Saturated fats are found in butter, coconut oil, palm oil, red meat, and processed meat.

- Trans fats in fried foods, margarine, baked goods, and frozen pizza.

- Added sugar often sneaks into sweetened coffee creamers, juice, soda, energy drinks, flavored yogurt, granola bars, and baked goods.

- Sodium foods like cured meats, potato chips, pretzels, popcorn, canned goods, and frozen dinners.

These targets should be personalized to you based on your diet, labs, medical history, medications, etc. Work with your cardiovascular dietitian who can assess your needs and create a personalized plan that helps you reach all of your heart health goals and targets based on your cardiovascular risk profile.

Other Risk Factors for Heart Attacks

It’s not just cholesterol that’s important to pay attention to when considering your cardiovascular wellness and heart attack risk. Here are some other factors involved:

- High blood pressure: This puts extra strain on the walls of your arteries, making them more prone to damage and plaque buildup. Over time, it can narrow or block arteries, increasing the risk of a heart attack.

- Sedentary lifestyle: Inactivity contributes to poor circulation, weight gain, and insulin resistance. It can also reduce heart efficiency and impair your body’s ability to manage cholesterol and blood pressure.

- Familial hypercholesterolemia: This inherited condition causes very high LDL levels from a young age, encouraging arterial plaque. It puts you at a significantly higher risk of having a heart attack early in life.

- Smoking: Smoking damages the lining of your arteries, encourages plaque buildup, and reduces oxygen delivery to your heart. It also increases clot formation, which can block blood flow and trigger a heart attack.

- Diabetes: Chronically high blood sugar or insulin resistance (which can occur for 10 years before a diabetes diagnosis) damages blood vessels and promotes inflammation, increasing heart disease risk.

- Obesity: Excess body fat, especially around the abdomen, raises blood pressure, cholesterol, and blood sugar, creating a metabolic environment that significantly increases heart disease and heart attack risk.

- Chronic stress: Even ongoing low-grade stress can increase blood pressure and inflammation. Stress triggers the release of hormones like cortisol, which can be harmful if it’s elevated for a prolonged time. Plus, when we’re stressed, we’re more likely to choose unhealthy coping behaviors like a poor diet or smoking, making things worse.

- Poor sleep: Inadequate or disrupted sleep interferes with blood pressure regulation and increases inflammation. Over time, these effects raise your risk of developing cardiovascular disease and having a heart attack.

- Inflammation: Chronic inflammation contributes to the development and rupture of arterial plaques, a trigger of heart attacks. It could also manifest as acid reflux, Hashimoto’s disease, or psoriasis.

Client Success Story

A 55-year-old woman came to see me because she had a CAC score of 144, indicating high levels of plaque in her coronary arteries. She was unsure why she had high plaque formation for her age, given she was active and led a healthy lifestyle.

Our initial evaluation revealed she had several risk factors that needed to be addressed to improve her risk of cardiovascular complications. When someone has a high CAC score and/or genetic susceptibility to premature heart disease, it is important to take a more proactive approach to risk modification to improve heart health and longevity.

Some of the factors discovered during our initial 90-minute assessment were her high cholesterol (LDL 126mg/dL, non-HDL cholesterol 142mg/dL) and high blood pressure (130/90s). Her BMI was considered healthy (23), however, she had an increased waist circumference (37 inches,) indicating underlying inflammation.

She was also on a laundry list of supplements that were not beneficial for her heart.

We worked closely together in my 1 on 1 program and within 3 months, her LDL cholesterol decreased by 53 points to 73mg/dL, her non-HDL cholesterol dropped by 55mg/dL to 87mg/dL, her blood pressure decreased to an average of 120/75mmHg, and her waist circumference decreased by 3 inches (34 inches = optimal!)!

We focused on optimizing her blood values and risk profile by adding therapeutic heart-healthy foods to lower artery-clogging cholesterol, improve blood vessel health and blood pressure, and address waist circumference.

We also decreased most of the supplements she was taking, as they were not beneficial for her heart health (even though they may often seem harmless). After our work together, she felt more empowered in her food choices and less fearful of her future.

High Cholesterol and Heart Attacks: Next Steps

While it’s not the only thing that matters, understanding your cholesterol levels and other cardiac biomarkers is essential for preventing a heart attack. Having high cholesterol is a direct risk factor because of how it contributes to narrowed arteries over time.

My 6-week cohort addresses everything you need to know about your heart disease risk factors, including each stage of the atherosclerosis process and how we can mitigate it through science-based nutrition.

Sources

- Schade DS, Shey L, Eaton RP. Cholesterol Review: A Metabolically Important Molecule. Endocr Pract. 2020 Dec;26(12):1514-1523. doi: 10.4158/EP-2020-0347. PMID: 33471744. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33471744/

- Wilkins JT, Li RC, Sniderman A, Chan C, Lloyd-Jones DM. Discordance Between Apolipoprotein B and LDL-Cholesterol in Young Adults Predicts Coronary Artery Calcification: The CARDIA Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016 Jan 19;67(2):193-201. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.10.055. PMID: 26791067; PMCID: PMC6613392. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6613392/

- Harper CR, Jacobson TA. Using apolipoprotein B to manage dyslipidemic patients: time for a change? Mayo Clin Proc. 2010 May;85(5):440-5. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2009.0517. PMID: 20435837; PMCID: PMC2861973. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2861973/

- Soliman GA. Dietary Cholesterol and the Lack of Evidence in Cardiovascular Disease. Nutrients. 2018 Jun 16;10(6):780. doi: 10.3390/nu10060780. PMID: 29914176; PMCID: PMC6024687. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6024687/

- Janapala US, Reddivari AKR. Low Cholesterol Diet. [Updated 2023 May 1]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK551722/

- Fuchs FD, Whelton PK. High Blood Pressure and Cardiovascular Disease. Hypertension. 2020 Feb;75(2):285-292. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.119.14240. Epub 2019 Dec 23. PMID: 31865786; PMCID: PMC10243231. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31865786/

- Park JH, Joh HK, Lee GS, Je SJ, Cho SH, Kim SJ, Oh SW, Kwon HT. Association between Sedentary Time and Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Korean Adults. Korean J Fam Med. 2018 Jan;39(1):29-36. doi: 10.4082/kjfm.2018.39.1.29. Epub 2018 Jan 23. PMID: 29383209; PMCID: PMC5788843. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5788843/

- Zhang Y, Dron JS, Bellows BK, Khera AV, Liu J, Balte PP, Oelsner EC, Amr SS, Lebo MS, Nagy A, Peloso GM, Natarajan P, Rotter JI, Willer C, Boerwinkle E, Ballantyne CM, Lutsey PL, Fornage M, Lloyd-Jones DM, Hou L, Psaty BM, Bis JC, Floyd JS, Vasan RS, Heard-Costa NL, Carson AP, Hall ME, Rich SS, Guo X, Kazi DS, de Ferranti SD, Moran AE. Familial Hypercholesterolemia Variant and Cardiovascular Risk in Individuals With Elevated Cholesterol. JAMA Cardiol. 2024 Mar 1;9(3):263-271. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2023.5366. PMID: 38294787; PMCID: PMC10831623. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38294787/

- Gallucci G, Tartarone A, Lerose R, Lalinga AV, Capobianco AM. Cardiovascular risk of smoking and benefits of smoking cessation. J Thorac Dis. 2020 Jul;12(7):3866-3876. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2020.02.47. PMID: 32802468; PMCID: PMC7399440. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7399440/

- Adeva-Andany MM, Martínez-Rodríguez J, González-Lucán M, Fernández-Fernández C, Castro-Quintela E. Insulin resistance is a cardiovascular risk factor in humans. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2019 Mar-Apr;13(2):1449-1455. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2019.02.023. Epub 2019 Feb 22. PMID: 31336505. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31336505/

- Emamat, H., Jamshidi, A., Farhadi, A. et al. The association between the visceral to subcutaneous abdominal fat ratio and the risk of cardiovascular diseases: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 24, 1827 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-19358-0

- Vaccarino V, Bremner JD. Stress and cardiovascular disease: an update. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2024 Sep;21(9):603-616. doi: 10.1038/s41569-024-01024-y. Epub 2024 May 2. PMID: 38698183; PMCID: PMC11872152. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38698183/

- Poor sleep linked to increased risk of heart attack and stroke. Nurs Stand. 2017 Apr 19;31(34):17. doi: 10.7748/ns.31.34.17.s20. PMID: 28421954. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28421954/

- Alfaddagh A, Martin SS, Leucker TM, Michos ED, Blaha MJ, Lowenstein CJ, Jones SR, Toth PP. Inflammation and cardiovascular disease: From mechanisms to therapeutics. Am J Prev Cardiol. 2020 Nov 21;4:100130. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpc.2020.100130. PMID: 34327481; PMCID: PMC8315628. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8315628/